BY STAS MARGARONIS

The National AHEPA Educational Foundation established the P.A. Margaronis Scholarship Fund as a result of a $1 million donation from Greek businessman and philanthropist, Pandelis A. Margaronis, who died in 2000.

In his life, P.A. Margaronis demonstrated the quality of character and innovation that immigrants and Greek-Americans have contributed to the growth of the United States.

It is this Hellenic-American spirit that AHEPA embodies.

The P.A. Margaronis Scholarship Fund, administered by the directors of the Educational Foundation for over twenty years, has supported AHEPA recipients who have demonstrated academic and extracurricular excellence, require financial support and are persons of Hellenic descent.

BACKGROUND & PATERNAL INSPIRATION

The donor of this fund, Pandelis Margaronis was born in Vrondados on the Greek island of Chios in 1914. His family subsequently moved to the Greek port city of Piraeus where Margaronis grew up.

Pandelis’ father Anastassios made his money operating sailing ships before transitioning to steam ships at the turn of the twentieth century.

P.A. Margaronis remembered life got harder for the family after the economic downturn accompanying the Great Depression of the 1930s:

“We moved house several time during that period. We never went hungry and we always had things, but it was always a struggle to make ends meet. My mother Maria was always struggling to make sure that we were well taken care of. For example, she would take my brother Christopher’s shirts which were passed down to me and when the collars of the shirts were too frayed, my mother would tear out the collars and re-sew them in upside down, giving the shirts extra life. Washing the sheets was a major production. The women would boil water in a tub and put the sheets in the boiling water to wash the sheets and clothes and then dry them out in the sun. There was no hot and cold running water in those days so if you wanted hot water for a bath the water had to be boiled and poured into a tub. Anything I got was usually a hand-me-down from my brother. My mother struggled to keep the house running and made sure that we wasted nothing…”

As a result of the Depression, Anastassios Margaronis was forced to go back to sea as a captain:

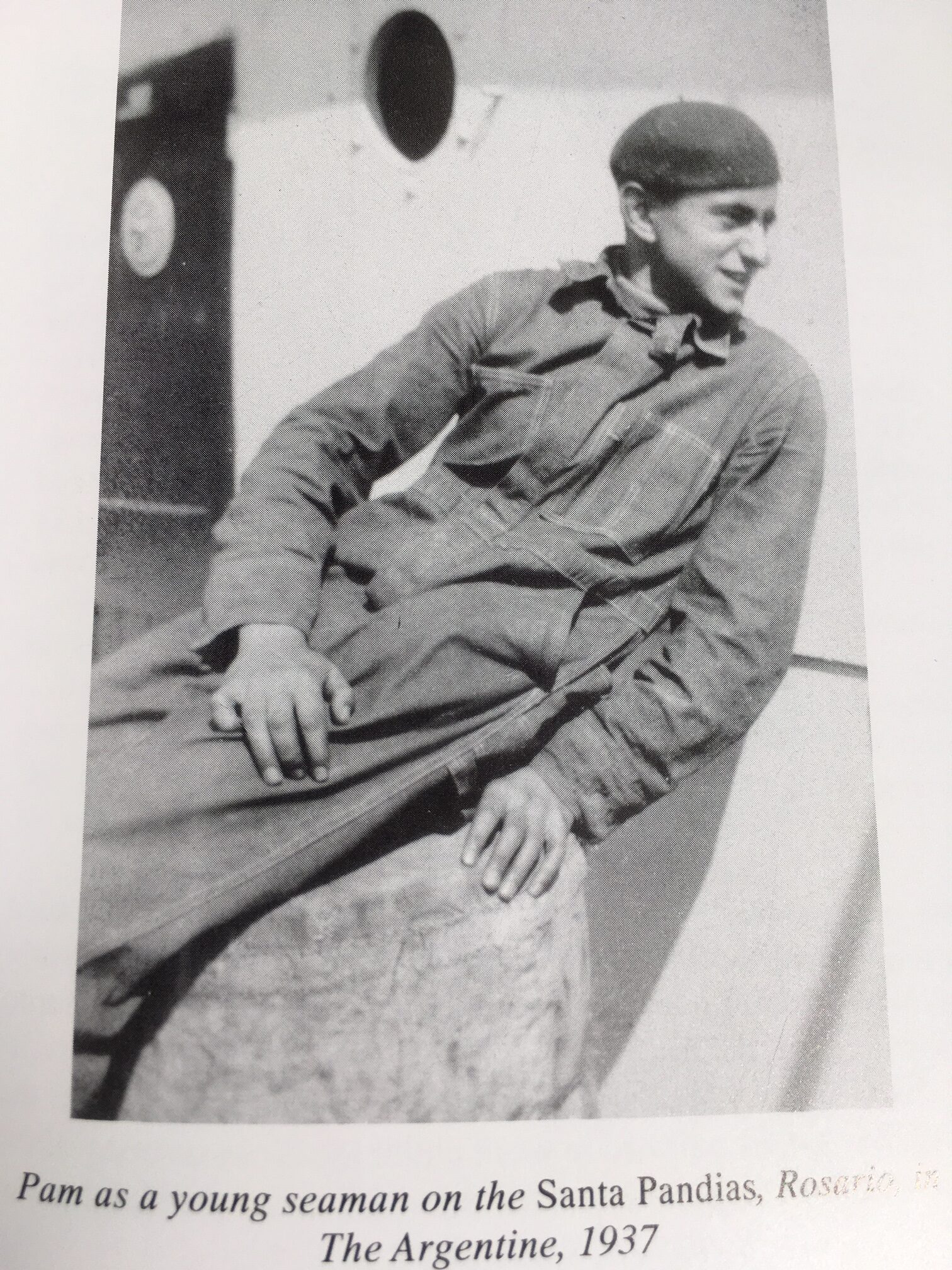

In 1934, when he was twenty, Pandelis went to sea with his father.

Margaronis recalled the impact on the wives and families of Greek mariners who were often away from home at sea for four years at a time:

“Life at sea was hard in those days. The average seaman was away from home for four years. His wife lived with the husband’s family or maybe with her own family and raised the children.”

Pandelis recalled that life on a Greek ship was tough on the mariner:

“On the ship, we each had our own bunk. There was no hot or cold water but you had boiled water generated from the steam engine. You had to buy your own rain gear, boots, plate, mattress and blankets.”

As there were no refrigerators, ships brought live animals onboard and used the grease from cooked meat for soap:

The hardships of the sea-going life built the characters of the next generation of shipowners:

“The Greek shipowner grew out of this era from the deck hands, engineers and captains who had lived through these times. They were successful in later life because they knew about the operations and the hardships of running a vessel from firsthand experience.”

The role of the captain was key to a voyage’s success:

“In those days a captain like my father had to be self-sufficient for everything. The revenues from the voyage had to pay for everything from provisions, to your fuel to the wages of the seaman which were 1 English pound a month at that time. What was left was the profit for the captain and the owners.”

Margaronis left the merchant marine to complete his military service in the Greek Navy.

After his service with the Greek Navy, Margaronis left Greece to join his sister Despina, who had married Demetris Fafalios and was living in Britain. There, he learned English.

WORLD WAR TWO ON THE NORTH ATLANTIC

When World War II broke out, he went back to sea as a deck officer on a ship owned by the Fafalios family:

“By mid-1941, Greece was occupied and out of the war. I got work as a second mate and I went to work for the Fafalios family.”

The life “of a merchant mariner sailing from North America to Britain during World War II meant you sailed in convoys with a military escort, but if you were torpedoed by a German U-Boat, you were on your own” adding:

“ I sailed on convoys supplying Britain during the war. Ships were being sunk because of the German U-Boats. The merchant ships were armed with small pop guns but they weren’t much use. I worked on a ship called the Stamos. It was a ship which always seemed to be having problems.”

There was the time the ship’s engine’s on the Stamos broke down and he and his crew were a sitting duck for a German U-Boat:

“ The engine of the Stamos broke down and the convoy had to leave us behind. We were sitting ducks if a U-Boat came along. We worked for three days to get that damn engine working again. Finally, we did. By the time we got to England the convoy had already arrived – or what was left of it. The convoy sailed straight into a German wolf pack and several ships were sunk. Only because the Stamos broke down did we miss that.”

ARRIVING IN THE NEW WORLD

In 1947, Pandelis, his Uncle Sideris and Sideris son Pandias Margaronis came to the United States with sufficient capital to buy surplus Liberty ships that U.S. shipyards mass-produced during World War II to transport food and weapons to war fronts in Europe and Asia.

While in New York, Pandelis met and fell in love with Athena Perdikakis, a dazzling dark-haired beauty who some said had movie star good looks. The couple married and settled in an apartment in the New York City Borough of Queens. Pandelis became a U.S. citizen and the couple had two children, Maria and Anastassios.

Arriving in the United States from war-torn Europe was like visiting another world for Pandelis.

During the War, he had seen Britain bombed by the German Air Force and arrived back home in Greece in 1946 to discover Greeks, including his parents, Anastassios and Maria as well as brother Christopher and sister Polyxeni, face near starvation from the German occupation. Partly as a result of malnutrition during the German occupation, his beloved mother Maria died in 1948.

Subsequently, his father Anastassios was kidnapped by communist fighters during the Greek Civil War of 1944-1948. He escaped execution when a sympathetic guard let him slip away from a group slated for execution.

Americans were lucky to miss the hardships endured by people in Asia and Europe during World War II, he believed.

Pandelis was also impressed with the opportunities for advancement for Americans and newly arrived immigrants to the United States, like himself. He believed, like many Americans, that if you worked hard and did a good job you could succeed in the U.S.A.

By 1948, the Margaronis family was building up its fleet of former Liberty ships.

As a result of improving post-World War II economic conditions and U.S. foreign aid to Europe, most prominently through the U.S. led Marshal Plan effort, economies in Europe prospered. And so did Greek and other European shipowners who profited from transporting goods generated by the growing North America to Europe trade.

BUILDING SHIPS IN JAPAN

By the mid-1950s, Pandelis Margaronis and his partners were looking to expand their fleet beyond the American Liberty ships and found an opportunity to order new ships from the growing efficiency of Japanese shipyards.

Margaronis was not only an early investor in low-cost Japanese built ships but he was a pioneer in switching over to more fuel-efficient diesel engines and away from less efficient steam engines. He also benefited from new designs to move the ship’s accommodations section from the middle of the ship to the ship’s stern section, thereby freeing up more space for cargo:

Due to changes in U.S. tax laws, Margaronis moved to the island of Bermuda, a tax-free haven.

While headquartered in Bermuda, Pandelis made plans to abandon Japan and build ships in Sevilla, Spain. The terms of construction were cheaper than Japan, but proficiency conditions with construction at the shipyard were costly and caused serious delays that undermined his effort to expand his fleet. He only succeeded in building one ship – a 20,000-ton bulk carrier, the Santa Alicia.

WORKING CONDITIONS AND THE RIGHT OF WORKERS TO BE REPRESENTED BY UNIONS

As a result of his experiences as a merchant seaman, Pandelis tried to make sure his mariners had good living and working conditions:

“I tried in building my ships to provide the crews with the best accommodations I could. They were certainly a hell of a lot better than the conditions I grew up with. The cabins were spacious, there was hot and cold running water, washing machines, refrigerators, good food, but I found that trying to be a good employer doesn’t always pay off. People will try to take advantage and when they try and take advantage you have to stop it or it will get worse.”

Pandelis Margaronis believed that workers had a right to form and be represented by labor unions:

“A machinist may be proficient with machinery, but when he needs to negotiate wages and working conditions, he needs professional representation to research and lobby for the best wages and working conditions. We business people have the money and resources to be represented by lawyers, lobbyists and trade associations, so why shouldn’t the worker be represented by a union?”

By 1980, Margaronis decided to retire from the shipping

business.

A NEW CAREER AS INVESTOR

He invested his shipping profits in an investment fund in

partnership with a maritime insurer.

As a result of high interest rates instituted by U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volker to combat high inflation in 1981, Margaronis was able to dramatically increase the value of his holdings within ten years by focusing investments in high yield bonds and re-investing the profits.

In 1982, Margaronis bought a condominium in North Palm Beach Florida where he lived for part of the year for the rest of his life.

He did not ever fully retire from work. He was buying and selling stocks and bonds until the end of his life.

AHEPA

By the late 1990s, Pandelis Margaronis faced the prospect of old age and death, he began to look for endowments to invest his wealth.

One of those beneficiaries was AHEPA and its educational fund.

Pandelis Margaronis entered into discussions with AHEPA Supreme President Johnny N. Economy after which he decided to make his bequest of $1 million to AHEPA.

Upon Margaronis’ death in 2000, Economy said: “We are deeply grateful to Mr. Margaronis, and his entire family, for their generous donation to the Educational Foundation … It allows AHEPA to meet its continuing commitment to our youth, and to our mission, by providing financial aid to deserving students in pursuit of their academic goals and dreams.”

In summing up the life of Pandelis Margaronis, his brother Christopher Margaronis said of him:

“Pandelis had a nickname in those days – ‘O’ Mavros’ – the black one – because he was so dark. He was totally incapable of saying no to anyone. He was always giving people the shirt off his back. He complains to me that he got a late start in business because he went to sea and because of the War. He got started when he was ready to get started and he did just fine.”